Academic Art

Academic Art

1 to 30 out of 46 artists

Paul Delaroche

1797 -1856, French / Romanticism and Academic Art, 27 works

Konstantin Yegorovich Makovsky

1839 -1915, Russian / Academic Art , Romanticism , and Realism, 417 works

Jean-Jacques Henner

1829 -1905, French / Academic Art, 402 works

Sir Frederic Lord Leighton

1830 -1896, British / Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Academic Art, 239 works

Jean-Georges Béraud

1849 -1935, French / Academic Art and Impressionism, 228 works

Frederic Remington

1861 -1909, American / Academic Art, 214 works

Delphin Enjolras

1857 -1945, French / Academic Art, 203 works

Thomas Hudson

1701 -1779, British / Academic Art, 199 works

Alexander Ivanov

1806 -1858, Russian / Academic Art, 114 works

Julius LeBlanc Stewart

1855 -1919, American / Academic Art , Impressionism , and Realism, 85 works

Alexandre Cabanel

1823 -1889, French / Academic Art, 81 works

Guillaume Seignac

1870 -1924, French / Academic Art, 69 works

Jules Joseph Lefebvre

1836 -1911, French / Academic Art, 65 works

Briton Riviere

1840 -1920, British / Realism and Academic Art, 62 works

Albert Joseph Moore, A.R.W.S.

1841 -1893, British / Academic Art, 61 works

Auguste Toulmouche

1829 -1890, French / Academic Art, 56 works

Ludwig Knaus

1829 -1910, German / Academic Art, 56 works

Herbert James Draper

1864 -1920, British / Academic Art, 55 works

Charles Sprague Pearce

1851 -1914, American / Academic Art and Impressionism, 45 works

Giulio Rosati

1859 -1917, Italian / Academic Art, 45 works

Solomon Joseph Solomon

1860 -1927, British / Academic Art, 38 works

Thomas Couture

1815 -1879, French / Academic Art, 34 works

Jean-François Portaels

1818 -1895, Belgian / Orientalism and Academic Art, 33 works

Paul Peel

1860 -1892, Canadian / Academic Art, 31 works

Charles Gleyre

1806 -1874, Swiss / Academic Art and Romanticism, 29 works

Ettore Tito

1859 -1941, Italian / Academic Art , Symbolism , and Realism, 24 works

Theodor Aman

1831 -1891, Romanian / Academic Art and Romanticism, 17 works

Christina Robertson

1796 -1854, Scottish, Female Artist / Academic Art, 16 works

Charles Martin Powell

1775 -1824, British / Academic Art, 15 works

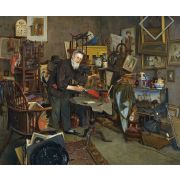

Charles Spencelayh

1865 -1958, British / Academic Art, 14 works

1 to 30 out of 46 artists

Academic art, also called "academicism" is a painting and sculpture style that grew in European art schools. In particular, literary art is the work of artists influenced by the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, active during the Neoclassicism and Romanticism movements. Academic art also includes the art that came after these two movements and tried to combine both styles, best shown in the paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart. In this context, it is often called "academism," "academicism," "L'art pompier," and "eclecticism," and it is sometimes linked with "historicism" and "syncretism."

On January 13, 1563, Cosimo I de Medici started the first art academy in Florence, Italy. It was influenced by the architect Giorgio Vasari, who gave it the name Accademia e Compagnia Delle Arti del Disegno (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing) because it had two different parts. The Company was like a business that any working artist in Tuscany could join. The Academy, on the other hand, was made up of only the most famous artists at Cosimo's court and was in charge of overseeing all of the state's art. At this medical school, students learned the "arti del disegno" (Vasari's term) and listened to lectures on anatomy and geometry. About a decade later, the Accademia di San Luca was started in Rome. It was named for St. Luke, the patron saint of painters. The Accademia di San Luca taught people and was more interested in art theory than the one in Florence. Annibale Carracci opened the Academy of Desiderosi in Bologna in 1582 without any help from the government. In some ways, it was more like a traditional artist's workshop, but he felt the need to call it an "academy," which shows how appealing the idea was at the time.

The Académie royale de Peinture et de sculpture, which was started in France in 1648 and later became the Académie des beaux-arts, was based on the Accademia di San Luca. The Académie royale de Peinture et de sculpture was started to separate artists, who were "gentlemen practicing a liberal art," from craftsmen, who did manual labor. This focus on the intellectual side of making art significantly affected the themes and styles of literary art.

Louis XIV reorganized the Académie royale de Peinture et de sculpture in 1661 to control all art in France. This led to a dispute among the members that changed how people thought about art for the rest of the century. In this "battle of styles," people disagreed about whether Peter Paul Rubens or Nicolas Poussin was better artist to look up to. Followers of Poussin, called "poussinistes," said that line (disegno) should be essential in art because it appeals to the mind. In contrast, followers of Rubens, who were called "Reubenites," said that color (color) should be essential in art because it appeals to the heart.