Dutch Golden Age

Dutch Golden Age

1 to 30 out of 33 artists

Jan Havicksz. Steen

ca. 1625 -1679, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 269 works

Jan van Goyen

1596 -1656, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 174 works

Aelbert Cuyp

1620 -1691, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 156 works

Salomon van Ruysdael

1600 -1670, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 140 works

Gabriël Metsu

1629 -1667, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 132 works

Gerard van Honthorst

1590 -1656, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 126 works

Adriaen van de Velde

1636 -1672, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 118 works

Ferdinand Bol

1616 -1680, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 102 works

Jan Lievens

1607 -1674, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 99 works

Jan Miense Molenaer

ca. 1610 -1668, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 93 works

Gerrit Dou

1613 -1675, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 90 works

Nicolaes Maes

1634 -1693, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 88 works

Pieter de Hooch

ca. 1629 -1685, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 80 works

Frans van Mieris the Elder

1635 -1681, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 76 works

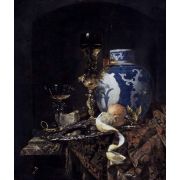

Willem Kalf

1610 -1693, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 54 works

Hendrick Terbrugghen

1588 -1629, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 53 works

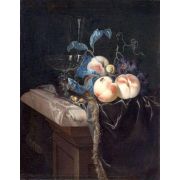

Willem van Aelst

ca. 1627 -1683, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 52 works

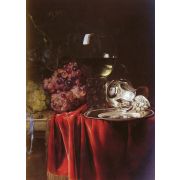

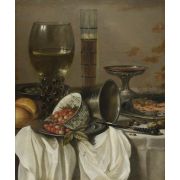

Pieter Claesz

1597 -1660, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 48 works

Simon de Vlieger

1601 -1653, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 45 works

Jacob Ochtervelt

1634 -1682, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 44 works

Hendrick Avercamp

1585 -1634, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 39 works

Pieter Codde

1599 -1678, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 39 works

Melchior d'Hondecoeter

1636 -1695, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 37 works

Isaac van Ostade

1621 -1649, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 36 works

Matthias Stom

ca. 1600 -1672, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 32 works

Salomon Koninck

1609 -1656, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 30 works

Adriaen van de Venne

ca. 1589 -1662, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 29 works

Pieter Saenredam

1597 -1665, Dutch / Baroque and Dutch Golden Age, 25 works

Dirck van Baburen

ca. 1595 -1624, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 24 works

Michiel van Musscher

1645 -1705, Dutch / Dutch Golden Age and Baroque, 17 works

1 to 30 out of 33 artists

The Dutch Golden Age is one of the best examples of how freedom led to Western cultural pride. During the 17th century, when the Dutch Republic was no longer under Spanish Catholic rule, its economy and culture increased. Due to an increase in trade, the business grew, and a large middle class and merchant class grew up selling the many works of art being made in response to the growing celebration of Dutch life and identity. The painting grew as artists focused on everyday scenes of ordinary life. These scenes were shown in many genre works, showing how creative the time was. Genre painting underwent a significant change, with many creative sub-genres that gave a unique look at the Dutch lifestyle, trends, and interests at the time. Subjects like fancy breakfast tables, group portraits, happy moments, and small details helped to create an artistic record of the time. Because of this, some scholars have called the painting style of the Dutch Golden Age "Dutch Realism."

During the Dutch Golden Age, landscape painting became very popular, focusing on the unique features of Dutch landscapes, villages, and rural life. This was a sign that Dutch values were becoming more respected. Many of these scenes were based on "heroic" things already in the area, like a tree, windmill, or cloudy sky.

Stilleven, or "still life," also became very popular. Artists used it to creatively show both beautiful things and the philosophical climate of the time by carefully arranging and grouping them. This important part of Dutch art grew into several subtypes, the most popular of which was the scientifically accurate floral still life.

The landscapes and village scenes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the anonymous Master of the Small Landscapes, and the work of Northern European Renaissance artists like Jan van Eyck, Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymus Bosch, and the Utrecht Caravaggisti all influenced Dutch Golden Age painting. But it was mostly a sign of how much the Dutch Golden Age dominated the time in terms of culture, economy, and science.

Frans Hals was one of the first painters of the Dutch Golden Age. He was a leader in both portraiture and genre painting. In 1616, he painted a group portrait called The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Militia Company, which made him famous. In the years that followed, he was in high demand as a portrait painter because he could make each person look real. He focused on a moment that showed the character and used natural light with visible brushstrokes to show movement. His genre work was also ahead of its time, as seen in Yonker Ramp and His Sweetheart (1623), which offers a cavalier and his sweetheart having fun. Many Golden Age painters, like Adriaen van Ostade, Adriaen Brouwer, and Judith Leyster, were influenced by him.

Even though the academy thought that historical painting, which included Biblical, mythological, and allegorical subjects, was the best painting, people in the Dutch Golden Age liked works about everyday things. Still, great works of historical painting, especially by Rembrandt, were made during this time. Initially, he was interested in history painting, but he became successful as a portraitist. His interest in history painting never went away, though, as his paintings Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer (1653) and Lucretia (1654) show (1666). The category also let him paint naked people, and Bathsheba Holding King David's Letter (1654), one of the few nude masterpieces of the time, is in this category.

When the French invaded the Netherlands in 1672, the Franco-Dutch War began. This was the beginning of the end of the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch broke the dykes and flooded much of the land to eliminate the invaders. Because of this, the Dutch still call 1672 "The Disaster Year." When the economy crashed, so did the art market, which hurt artists like Vermeer, who went bankrupt. By the time the war was over in 1678, the Dutch had lost a lot of power, and the art market had never improved.

Still, Dutch genre paintings affected French artists like Jean Siméon Chardin, Jean Baptiste Greuze, and Jean Honoré Fragonard as the French Rococo style took over in the early 1700s. But from the late 17th century to the early 18th century, the works of many Dutch masters, such as Rembrandt, Hals, and Vermeer, fell out of favor. As classical elegance became more popular, Hals's brushwork was called sloppy, and Rembrandt's rough-hewn humanism made people angry.

During the Romantic movement in the early 1800s, Rembrandt was rediscovered. The critic William Hazlitt called him "a man of genius" who "took any object, no matter how simple in shape, color, or expression, and made it beautiful by the light and shadow he put on it." So, Rembrandt told Eugene Delacroix and J.M.W. Turner about his "veil of matchless color," as Turner called it. Throughout the 19th century, artists like Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Rodin, and Thomas Eakins were influenced by him. In the 20th century, Pablo Picasso, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, and many others were affected by him.

In the late 1700s, John Constable found Jacob van Ruisdael again. Constable owned four of the artist's etchings and copied several of his works. After that, the Barbizon School and the Hudson River School drew a lot of inspiration from Van Ruisdael's landscapes.

In 1842, art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger rediscovered Vermeer, whom he called "the Sphinx of Delft," along with other Dutch Golden Age painters like Hals and Carel Fabritius. Because of this, many artists, like Gustave Courbet, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Claude Monet, were influenced by the artist's realistic paintings of everyday life and the effects of light. Hals's rough style significantly impacted artists like Manet and Courbet of the Realist movement, as well as Monet and Mary Cassatt of the Impressionist movement.

Also, Dutch still lifes significantly impacted Western art, as the subject stayed famous well into the modern era, as seen in the works of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, Emil Nolde, Giorgio Morandi, and Henri Matisse. The Barbizon School, the Hudson River School, Tonalism, and Luminism grew out of Dutch landscape painting.